Alcatraz has always been more than concrete

and cold water—it’s been a riddle wrapped

in razor wire, soaked in fog and legend. For

decades, the world has stared at that jagged

island in San Francisco Bay, asking

the same question: Did they make it?

Now, in 2025, a new twist has surfaced—one

so precise, so calculated, it’s turning old

assumptions inside out. But don’t expect a tidy

ending. This isn’t about heroes or villains. It’s

about shadows, science, and a silent night

that still echoes with secrets. What really

happened beyond those cell walls? And how close

have we come, until now, to finally knowing?

Inside America’s Most Secure Prison

Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary,

often referred to simply as “The Rock,” stood as

a symbol of the U.S. government’s most extreme

approach to incarceration. Located on a small

island 1.25 miles off the coast of San Francisco,

Alcatraz was originally a military fort during

the eighteen-fifties before being converted into

a federal prison in 1934. Managed by the Federal

Bureau of Prisons, it was designed to house

inmates deemed too disruptive or dangerous

for other facilities. From its inception,

Alcatraz was intended to be the “end of the

line”—a maximum-security, minimum-privilege

institution for the most incorrigible offenders.

The prison facility itself was a feat of

engineering and security. The main cellhouse,

constructed between 1910 and 1912, featured

four blocks of cells, a dining hall, a hospital,

a library, and administrative offices. The cells

were small, bare, and built with tool-proof steel

bars. Prisoners were counted up to 13 times a day,

and the ratio of guards to inmates was

the lowest in the nation. Metal detectors,

tear gas canisters, and armed guards in elevated

gun galleries enhanced security at every turn.

Access to privileges like work, visitation, and

even talking during meals had to be earned, making

daily life both strict and psychologically taxing.

With its inmate capacity of about 312, Alcatraz

rarely got filled to that total. It accommodated

some of the known worst criminals, Al Capone and

“Machine Gun” Kelly. Super-maximum offenders were

dispatched to D-Block, home to “The Hole,” some

isolation cells infamous for inhumane conditions.

It was a strictly racial segregation, with no

rehabilitation intended, only control. There

had been major upgrades in the functioning of

the prison during its 29 years in operation, like

the introduction of electrified fences, updated

locking systems, and renovations to improve

security in the nineteen-thirties and forties.

Alcatraz was closed down on March 21, 1963, mainly

because of the high cost of maintenance and the

dilapidated state of the buildings, owing to

weakening saltwater corrosion. And yet, it

is this legacy that captures imagination. Today,

managed by the National Park Service as a museum,

it has more than a million yearly visitors.

Refurbished areas provide an introduction to what

used to be deemed the toughest penitentiary in the

United States: a stronghold where the thin line

separating punishment and survival often blurred.

Its walls were strong, but its legend was even

stronger… until one night changed everything.

The Myth of the Inescapable Rock

Alcatraz wasn’t just a prison—it was a symbol.

Perched on a wind-battered island in San Francisco

Bay, it came to represent the final word in

American incarceration. Not just a place to

serve time, Alcatraz was where the system sent

inmates it had given up on. The prison’s design,

its isolation, and its relentless

routines created a legend: that escape

was not only impossible, but unthinkable.

That belief wasn’t based on folklore—it

was reinforced by statistics. Over its

29 years of operation, no one had ever

been confirmed to have escaped. In 14 recorded

attempts, most were captured or slain, with a

few vanishing into the waters, presumed drowned.

The treacherous tides, frigid temperatures, and

sheer distance from shore made the bay itself an

unbreachable final barrier. To attempt escape was,

by most standards, to sign one’s death warrant.

This image, totally contained, was essential

for Alcatraz. It was not just about locking

people up: it was about annihilating any idea

of escape. Guards, officials, and the public

bought into the myth of “The Rock” being

impossible to escape from, and that myth served

the prison’s power. That power came under stress

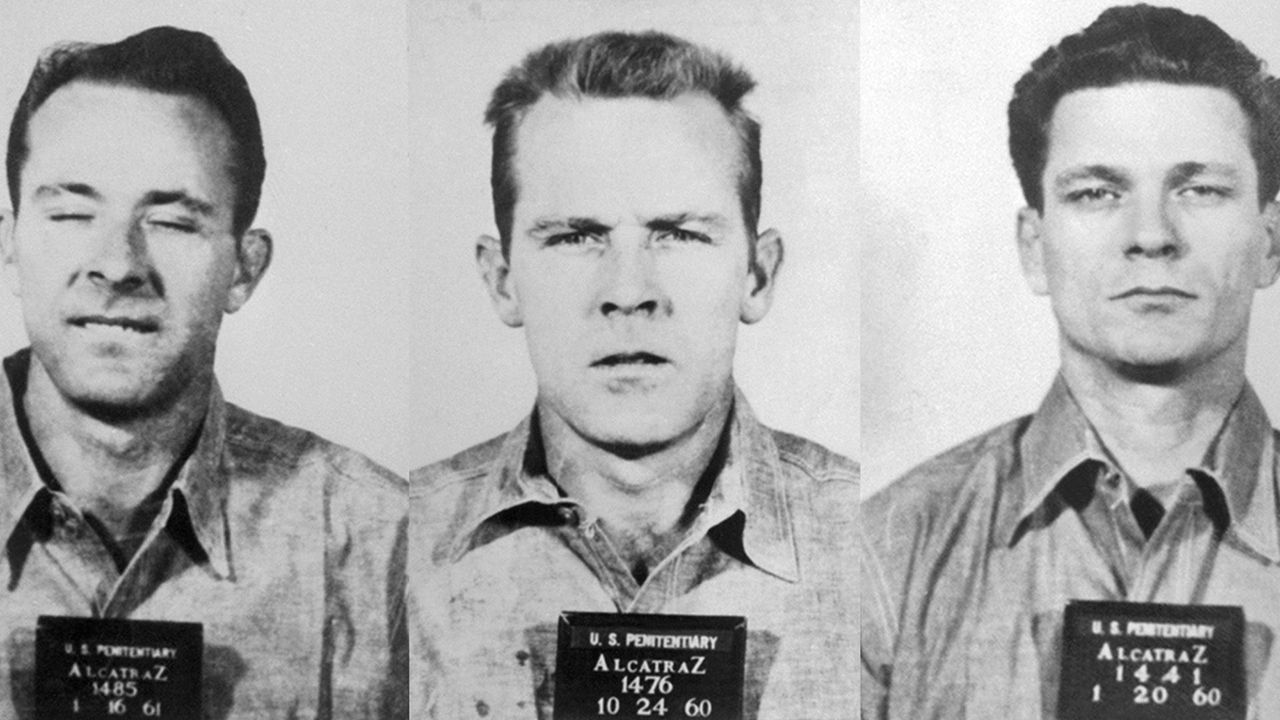

in June 1962. Sometime between 10:30 and 11:00

p.m. on June 11, 1962, three inmates were to

get out of their cells and disappear: Frank

Morris, John Anglin, and Clarence Anglin.

The escape caused an introspection. The moment

Alcatraz was said to be outfoxed even once,

it was taken off its pedestal. The

psychological aftershocks were immediate; once there had been a fortress, now there was

only mystery. But this time, unlike others,

the enigma lingered on. Now, the lack of a

definite conclusion planted seeds of doubt,

then fascination, and finally a tale grander than

the prison itself. To this day, the 1962 escape is

not merely an event—it is a fulcrum in the mythos

of Alcatraz. The question of whether those men

lived or died remains a mystery; what is known is

that their very disappearance cracked America wide

open from a myth she’d carried for decades. That

crack in The Rock allowed the legend to seep away.

Frank Morris: The Genius Behind the Plan

Frank Lee Morris was far from an average

inmate—he was a seasoned criminal with a

brilliant mind and a history of escapes,

the kind of man Alcatraz was specifically built to

contain. Orphaned at age 11 and convicted by 13,

Morris spent most of his youth moving between

foster homes and institutions. His early life

of instability hardened him, but it also

sharpened his instincts. With a criminal

résumé that included armed robbery, substance

possession, and multiple successful escape

attempts, Morris was transferred to Alcatraz in

January 1960 after fleeing the Louisiana State

Penitentiary. From the moment he arrived, he

was already thinking about how he would leave.

Once at Alcatraz, Morris was placed near fellow

inmates John and Clarence Anglin, as well as Allen

West—all of whom he had previously encountered

during time served at other prisons. With their

cells side by side, the men could whisper to

each other at night, quietly forming what would

become one of the most calculated escape teams

in history. Morris naturally assumed the role of

leader. His intelligence and prior experience

escaping prison made him the architect of the

plan that would ultimately shake the reputation of

Alcatraz to its core. Unlike others who had tried

and failed, Morris aimed for flawless execution.

The group spent months hacking away at the salt

damage of concrete beneath the vents under

their sinks. They had stolen metal spoons,

discarded saw blades, and homely built the drill

powered by a vacuum cleaner to make holes in the

deteriorating concrete material. Morris produced

papier-mâché grilles painted with stuff he stole

from the library and maintenance shop to mask

their activities. Even the sounds of their

drilling have been dealt with: Morris played his

accordion during “music hour,” using its wheezing

sound to cover the noise from the digging

activities. There is no improvisation here;

most definitely, there is planning, testimony

that indeed Morris is tactically brilliant.

The very act of breaking free was not merely a

prison breakout but rather a direct challenge

to the myth of Alcatraz’s invulnerability. By

sewing together more than 50 raincoats into

a 6 by 14-foot raft and life jackets, using hot

steam pipes to seal the hunk of rubber, Morris

and the Anglin brothers defied even gravity. They

even converted a concertina into a makeshift air

pump. They officially supposedly drowned, but no

bodies were recovered, and 2013 letter contains

some compelling evidence to the contrary. Whether

Morris died in the bay or lived a secret life in

hiding, his escape was undeniably the cleverest

escape in Alcatraz’s 30-year history, proving that

even “The Rock” could be cracked.

The Anglin Brothers John and Clarence Anglin were more than just two

inmates serving time—they were brothers bound by

hardship, loyalty, and a relentless desire

to be free. Born into a poor farming family

in rural Florida, they were part of a large

brood of 13 siblings and grew up learning how

to survive together. That bond of brotherhood

became the foundation of their infamous escape

from Alcatraz. Their lives of crime, mostly

centered around bank robberies, landed them

in the Atlanta Penitentiary, where their repeated

escape attempts became such a problem that prison

officials finally sent them to Alcatraz—the

supposed end of the line for troublemakers.

It was at Alcatraz that the Anglins were reunited

with Frank Morris, whom they had met in earlier

stints behind bars. The brothers were placed in

adjacent cells next to Morris and Allen West,

which allowed them to communicate and

collaborate covertly. With Morris as the brains

of the operation, the Anglin brothers became

indispensable hands in the escape effort. Over

months, they helped dig holes through decaying

concrete, using metal spoons and saw blades.

While Morris led the engineering side of the plan,

the Anglins worked on logistics and concealment,

making papier-mâché vent covers to

disguise the holes and gathering materials from their prison labor assignments.

That, too, basically, helped them in preparing

the escape equipment for their escape.

They had also helped Morris prepare the life jackets and one gigantic raft of 6 by 14

feet from more than 50 reused stolen raincoats.

The hot steam pipes of the prison sealed rubber,

while a modified concertina was used to inflate

the raft into an air pump. Important, too, to

know the daily activities of the prison-and

accessible materials through the factory system.

But every movement they made was calculated, the

course taken was carefully shielded from another

well-built illusion, including the iconic dummy

heads they helped sculpt from soap, toilet paper,

and real hair swept from the barber shop floor.

The events that followed their disappearance

are among the most fascinating mysteries of American criminal history. Evidence has surfaced

supporting the idea of the two brothers having

lived even after the 1979 legal pronouncement of

their deaths. Besides the 2013 letter claiming

they had been hiding, there were alleged

Christmas cards from the brothers confiscated,

and even a 1975 picture that seemed to show

them in Brazil. BBC Interview prison officers

and family reminisced about this incident as

shocking and eerily quiet, there were no sounds,

no alarm raised by night. If the Anglins survived,

they pulled off not just a physical escape, but a

psychological one-dimming out of a prison made to

be inescapable, and out of even history itself.

Crafting the Illusion

The brilliance of the 1962 Alcatraz escape wasn’t

just in the digging or raft-building—it was in

the illusion. One of the key elements that allowed

Frank Morris and the Anglin brothers to vanish

undetected was the creation of eerily lifelike

dummy heads. These decoys were so convincing

that they fooled guards doing regular headcounts.

Sculpted from a bizarre mix of soap, toothpaste,

and toilet paper, the heads were carefully molded

to resemble sleeping inmates. The escapees painted

them in flesh tones using art supplies stolen from

the prison maintenance shop and topped them with

real human hair, swept from the barbershop floor.

These heads weren’t just clever—they

were critical. During nightly checks, guards didn’t physically shake prisoners awake;

they simply looked into cells for movement.

The dummies, placed on the pillows and partially

hidden under blankets, gave off the perfect

illusion of slumber. To complete the deception,

the escapees bundled clothes and towels beneath

the sheets to mimic the shapes of sleeping

bodies. The effect was so flawless that it

wasn’t until the morning roll call on June

12 that the guards realized something was

wrong—by then, the trio had been gone for hours.

Deception went beyond the dummy heads and included

caverns extending into the walls. The prisoners

used cardboard and papier-mâché covers made from

torn magazine pages from the prison library to

make holes that had been being dug for months,

all the while the prisoners were camouflaging

the holes; these fakes resembled the air vent

grilles at the back of their cells. These

false grilles blend well into the wall,

hiding behind them the escape route, which hails

gaping. The guards, peeking into the cells,

would just see what would seem to be an

absolutely normal sealed vent, where,

in reality, a tunnel to freedom waited behind.

The more remarkable thing about the illusion is

its resonance with the larger tradition

of psychological warfare behind bars,

the art of deception cultivated by desperate men

in desperate places. In fact, all over the world,

deceptions have aided in imprisonment breaks-from

letters smuggled in hollowed-out books to false

uniforms sewn from laundry scraps. Yet, few will

compare to the Alcatraz ruse in terms of detail

and showmanship. The FBI agent who worked on the

case, Michael Dyke, remarked, “They didn’t just

dig out; they rehearsed a performance,” indicating

that the escape involved the psychological as much

as it did the physical. The escapees set a scene

that beguiled not only the guards but the entire

prison system; their cells became a stage on that

night, and for a few hours, the escapees were

actors playing the ghostly role of disappeared.

But deception was only the beginning—the real

escape began beneath the surface.

Digging to Freedom

The foundation of the Alcatraz escape plan was

literally carved into the crumbling infrastructure

of the prison. Frank Morris, John and Clarence

Anglin, and Allen West exploited a critical

vulnerability—salt-damaged concrete behind the air

vents beneath their sinks. Over several months,

the men slowly chipped away at the weakened

material using tools that were as simple as they

were ingenious. They stole metal spoons from the

dining hall and repurposed discarded saw blades.

Even more impressive was their homemade drill,

crafted from a vacuum cleaner motor. Bit by bit,

night after night, they carved escape tunnels that

would open into an unguarded maintenance corridor.

What made this feat possible was not brute force

but extreme patience and surgical precision. The

men worked carefully to avoid detection, placing

cardboard covers and papier-mâché vent grilles

over the holes during the day. These grilles were

painted to match the wall using art supplies from

the prison library, allowing them to blend in

flawlessly with the surroundings. The escapees

coordinated their digging to coincide with “music

hour,” a daily period when instruments could be

played. Morris’s accordion—noisy and wheezy—masked

the sounds of scraping and drilling, transforming

the cellblock into a covert construction zone.

Once the holes were large enough to crawl through,

the escapees entered the unguarded corridor and

went upstairs to an empty upper level of the

prison, where they built a hidden workshop. Here,

they stored materials and worked on other escape

elements: the raft and paddles. Entering this

section was made easier due to the deteriorating

conditions of the prison, which sits on the

relics of the former military fortifications.

Some old prisoners and later investigators

would recall how the foundational layers

of Alcatraz were “rotting and breaking up,” just

giving those few men an edge to work undisturbed

in those old-sized maintenance tunnels.

One of the most crucial final errands

was to access the ventilation shaft at the very

top of the block. The men climbed 30 feet using

plumbing pipes and pried the vent cover. Then, to

avoid suspicion, they molded a false bolt out of

soap and sealed the grate. Yet another instance

of spare detail. By the time the escapees made

their move, they had literally worked an intricate

path from their cells to the roof. Their strategy

concerned much more than just getting out; it

was using the prison’s own overlooked weaknesses,

its age and design, against it. And having done

so, they managed what nobody else was able to do:

an undetected, almost surgical,

tight escape route out of the Rock.

The Raincoat Raft and the Icy Bay

With their escape tunnel complete and the prison’s upper levels successfully

navigated, Frank Morris and the Anglin brothers

still faced their most daunting obstacle—the

icy, unforgiving waters of San Francisco Bay.

Temperatures hovered between 50–55°F, and the

currents were notoriously strong. It was these

very conditions that had long cemented Alcatraz’s

reputation as “inescapable.” But Morris and the

Anglins weren’t just breaking out of a cell—they

were escaping an island fortress. To do it,

they had crafted a homemade raft and life

vests using over 50 stolen raincoats,

a feat of prison engineering that demonstrated

just how far their determination reached.

The raft itself measured approximately 6 by 14

feet and was constructed in a makeshift workshop

the escapees had set up above the cellblock.

The raincoats were stitched together using

thread taken from the prison’s work areas, and

the seams were sealed by melting rubber with

steam pipes found within the prison’s

plumbing system. To inflate the raft,

they converted a concertina (similar to a small

accordion) into a makeshift air pump. Even the

paddles were homemade, fashioned from bits of

plywood, likely salvaged during their work duties.

Everything they needed to challenge

the bay had been hidden in plain sight. After months of meticulous planning, the trio

was finally at the northeastern shore of the

island on the night of June 11, 1962. There, they

inflated and launched the raft into the darkness,

welcoming the chance to travel to the distant,

under-two-mile-away Angel Island. While the

escape went silent until the next morning,

it slowly gave away clues about its journey.

A paddle was uncovered by the Coast

Guard on June 14. On the same day,

a sealed parcel containing the Anglin brothers’

personal effects was found. One week later,

pieces of the raft drifted ashore by the Golden

Gate Bridge, followed by a homemade life vest.

However, these materials have failed to produce a

trace of the men. Numerous officials, such as the

prison warden, continued to be convinced that

the escapees had drowned. “You hear the wind,

don’t you? And do you see the water?” asked

then-Warden Richard Willard in a BBC interview.

“Do you think you could make it?” Chambers

believed, however, that the sophistication of

the raft and precision of the escapees led to

the conclusion that they might have survived.

Subsequent scientific analyses had further

indicated that if at all the escape were launched

during a narrow tidal window, such an escape could

be successful. Whether the bay swallowed them or

they made it to freedom, the raincoat raft remains

the most innovative symbol of defiance against the

most secure prison America had ever built.

Allan West: The Man Left Behind

Allan West was originally one of the four inmates

who helped plan the great Alcatraz escape,

but he ultimately never made it out. A

longtime prisoner at Alcatraz since 1957,

West had known Frank Morris and the Anglin

brothers from previous prison stints, and their shared time in neighboring cells allowed

them to hatch the plan together. West was involved

in every stage—chiseling through the weakened

wall behind his sink, helping gather materials

for the raft and dummy heads, and contributing to

the construction of the escape route. But on the

critical night of June 11, 1962, West couldn’t

break through the last bit of concrete in time.

According to his own confession, West’s tunnel was

just too narrow. He had miscalculated the size or

failed to fully remove the last section of cement.

As he struggled to widen the opening in a panic,

the others couldn’t wait any longer.

With time ticking and dawn approaching,

Morris and the Anglin brothers proceeded without

him. West remained in his cell, fully aware that

his once-in-a-lifetime opportunity was slipping

away. His fate was sealed not by fear, but by the

smallest of physical obstacles—the last few inches

of crumbling concrete that just wouldn’t give.

The next morning, the guards found that

an escape had taken place and immediately

thereafter West cooperated with law enforcement

officials. He provided a detailed description of

the escape scheme, outlining the path to the

utility corridor, the route over the rooftop,

and their intended end point, Angel Island. His

testimony became the basis for the subsequent

manhunt. According to the BBC, it led West

to point to evidence such as a paddle and

belongings belonging to the Anglins. However, none

of the escapees were ever found, which gave rise

to suspicions that they had the presence of West

in mind during their escape and had changed their

route so as to prevent capture if he talked.

Allan West had to carry the burden of a plan

nearly implemented. While he escaped the risk

of freezing to death in the treacherous waters,

he forfeited the opportunity of escaping to

freedom. Following the foiled escape attempt,

West was processed when Alcatraz closed its doors

in 1963 and completed its sentence. While often

overshadowed by those who seemed to vanish, his

role was central in the escape in providing the

most complete insider account of it. In the mythic

narrative of Alcatraz, West stands as a witness on

earth to a flight that just might have succeeded.

A Chilling Confession or Clever Hoax?

In 2013, more than 50 years after the escape that

stunned the world, a new twist reignited interest

in the Alcatraz mystery. A letter, allegedly

written by John Anglin, was sent to the San

Francisco Police Department. It read, “I escaped

from Alcatraz in June 1962. Yes, we all made it

that night, but barely!” The letter claimed that

Frank Morris had died in 2005, Clarence Anglin in

2008, and that John himself was terminally

ill and willing to negotiate his surrender

in exchange for medical treatment. The message

sparked a new wave of speculation and prompted

law enforcement to take a closer look at a case

that had been considered closed for decades.

The FBI quietly launched a renewed investigation.

The letter underwent forensic scrutiny—handwriting

analysis, fingerprint, and DNA testing

were conducted to determine whether the

confession could be legitimate. Yet, despite

the effort, the results were inconclusive.

The handwriting didn’t match definitively with

known samples from the Anglins or Morris, and no

usable DNA or fingerprints could be confirmed.

This ambiguity left the case suspended between

belief and doubt. The letter was credible enough

to suggest it could be real, but lacked the hard

evidence necessary to prove its authenticity.

The general populace remained ignorant of the

letter’s existence until 2018, when the story

was broken by local CBS affiliate KPIX. The

timing and contents of the letter, along with

decades of alleged sightings and family claims,

provided introductory oxygen to a mystery that

will not die. Even prior to the letter surfacing,

the Anglin family claimed to have received

Christmas cards from the brothers, and there was a much-debated 1975 photograph allegedly showing

John and Clarence in Brazil. The text of the

letter, with its chilling reference to surviving,

traveling across states, and living a quiet life

in hiding, could perhaps be the most compelling

evidence yet that the escape may have worked.

The U.S. Marshals Service, technically still

holding the case, has left all doors open. Only

recently, in 2022, did it come out with new

age-progressed renditions of how Morris and

the Anglin brothers might look today, with public

appeals for possible new leads. Some investigators

and officials remain convinced that the men died

in the Bay, but others think there are just too

many unanswered questions for the case to be

considered closed. Whether true confession or

elaborate hoax, the 2013 letter underlines tomes

of the Alcatraz legend-and probably has brought us

closer to the truth than any letter ever had.

Particularly riveting about the 2013 letter

is how it integrates into a larger cultural

fascination surrounding vanished criminals

and unsolved myths. In our time of maximum

surveillance, near-absolute digital footprints,

and mostly low public interest, it seems almost

mythological that three men might have disappeared

after committing a crime—blending into the shadows

for decades, so to speak. The aforementioned

evokes romanticized legends of many- D.B. Cooper;

why not Billy the Kid- criminals-turned-popular

culture folk. An old adage, “When the underdog

could beat the system, people love a good

mystery,” quotes Michael Dyke, a former U.S.

Marshal, during one of his interviews in 2016.

This attraction is not only because of the

theory that these men might have survived; it also speaks to the very philosophy of a few

rotten cracks in an otherwise rigid institution,

where a slip of freedom remains possible.

Just when the trail seemed cold, science found

something the myths never could…

Science vs. Skepticism

For decades, the prevailing belief held by prison

authorities and federal investigators was that

Frank Morris and the Anglin brothers didn’t

survive their escape attempt from Alcatraz.

The cold, swift waters of San Francisco Bay

were seen as an impenetrable natural barrier.

Warden Richard Willard echoed this sentiment

during a 1964 BBC interview, asking pointedly,

“Do you think you could make it?” Like many at

the time, he believed that even if the men had

managed to leave the island, the water would

have claimed them. It was this belief that

supported the FBI’s decision to close the case

in 1979, declaring the escapees legally dead.

But in the decades since, that hard line has been

increasingly challenged by science. In 2014, a

group of Dutch researchers used advanced computer

modeling to reconstruct the tidal conditions of

the night of June 11, 1962. They found that

if the escapees launched their raft between

11 p.m. and midnight—a window that coincides

with the estimated time of departure—they

could have been carried by the currents toward

Angel Island. This simulation contradicted the

long-standing narrative that the waters were

insurmountable, offering a feasible survival

scenario if the men were precise in their timing.

The scientific leap rekindled interest and cast

fresh light on decades of rumors and supposed

sightings. In the wake of the findings from the

Dutch study, the 2013 letter claiming the men

survived and lived reclusive lives gained fresh

traction. Together with evidence discovered—the

recovered paddle and its personal effects as well

as bits of the raft—it was now plausible that the

men might have reached shore alive. Not even the

escape was physically possible; it might have

worked if executed with the level of detail the

men displayed throughout the rest of their plan.

As evidence and science mount behind the case,

however, to the U.S. Marshals’ discredit, they

have determined that a convict, like Morris and

the Anglins, would have all together vanished

into quiet law-abiding lives. Nevertheless,

the file remains open: as recently as 2022,

updated age-progressed photographs were released

of the three, which implies that law enforcement

has not quite thrown in the towel at finding the

fugitives. Science may have found the true,

or incomparably real, hidden under that fact:

the escape from Alcatraz stands as one

of America’s most fascinating unsolved

mysteries—a tale where fact and possibility

still wrestle for dominance. In addition to

tide charts and forensic reconstructions, the

old curiosity about the Alcatraz escape is

something much deeper in American culture:

a national obsession with outsmarting the

system. From books to Hollywood films like

, the story has

been mythologized not as a prison break but as a

tale of human ingenuity over institutional power.

Think they made it out alive? Or did the bay claim

them for good? Let us know your theory in the

comments below! If you enjoyed the mystery, give

this video a like, hit subscribe for more true

crime and history deep dives, and don’t forget to

tap the bell so you never miss what’s next. Now,

check out the next video on your screen—you

won’t believe what was uncovered there.